On 04 February, few noticed the passing of the anniversary of the Philippine-American War (which is known as the Philippine Insurrection in the United States). By and large, the war has become a mere footnote in history, which is not really surprising as the Philippines has become one of America’s closest allies in the Asia Pacific region. Filipinos also like to emphasize their colonial links to the United States as a selling point to attract business process outsourcing (BPO) investments. If they were alive today, Theodore Roosevelt and William McKinley would be proud. Their theory of how the White Man would turn the Little Brown Brother into a Civilized Being through a policy called Benevolent Assimilation has just been validated.

THE PROTAGONISTS

These memories remind me of the commonalities of the historical experience between the Philippines and Cuba. Even the actors and personalities who played in the grand historical drama were the same. Many Spanish military commanders cut their teeth in both Philippine and Cuban Theaters of War as both colonies near-simultaneously rose up in revolt. Conversely, many of American veterans of the Cuban campaign would later turn up in the Philippines when the Philippine-American War flared up.

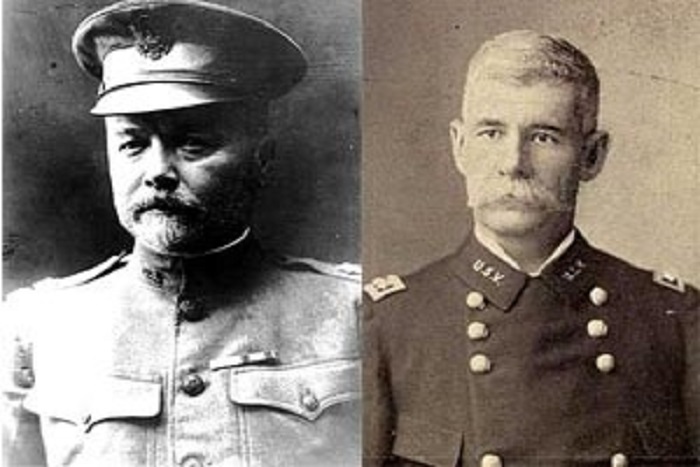

Common Spanish adversaries who both served in the Cuban and Philippine Theatres of War include: Valeriano Weyler Nicolau, Camilo Garcia Polavieja, Jose Lachambre Dominguez, Ramon Blanco Erenas, Juan Arolas Espluguees, Ernesto Aguirre Bengoa, Luis Daban, Joaquin Vara del Rey, Sabino Gamir, and Antonio Zabala.

Blanco Erenas, a former Spanish Governor General in both Philippines and Cuba, ordered the exile of Philippine National Hero, Dr. Jose Rizal, to Dapitan and approved his departure to Cuba as a volunteer doctor.

Garcia Polavieja was one of the most ruthless protagonists against the Independence Movements in Cuba and the Philippines. He ordered the execution of Rizal.

Lachambre Dominguez, for whom Plaza Lachambre in Manila’s district of Binondo is named, is perhaps one of the most outstanding Spanish military tacticians who served in both Cuba and Philippines. Lachambre executed a masterful military operation in Cavite which eventually pressured Filipino rebel leader Emilio Aguinaldo into exile in Hong Kong.

One particular name stands out. That of Spanish General Weyler Nicolau, whose brutal tactics in the Philippines in 1895 and Cuba in 1897 earned him the sobriquet “the Butcher.” Weyler was known for being the first military commander in the modern era to employ the tactic of hamleting or concentration camps. While Weyler is mostly known for his bloodthirsty reputation, he earned a somewhat positive distinction for advancing the native Filipino women’s rights to education despite the objection of the then-omnipotent (or still is) Catholic Church of the Philippines .

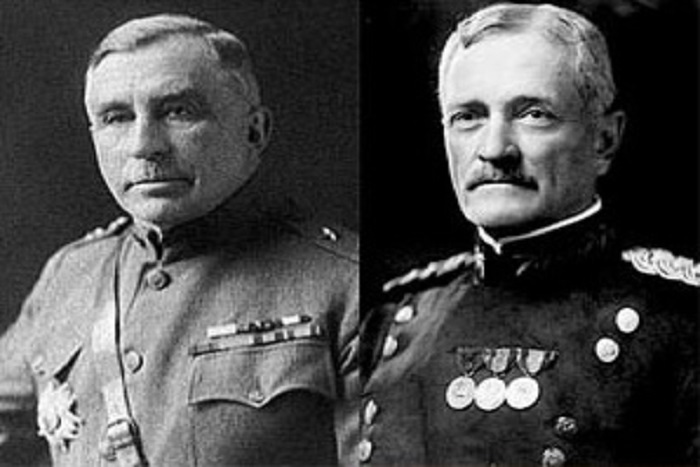

Notable American soldiers who fought and distinguished themselves in both Theaters of Operations include such luminaries as Henry Ware Lawton, Frederick Funston, John Joseph Pershing and Leonard Wood.

Lawton earned his fame during the Indian Wars by capturing the Apache chief, Geronimo. In a cruel twist of fate, he would later die from the bullets of an insurgent sniper under the coomand of a Filipino General named Licerio Geronimo. He was the highest ranking American officer to be killed in the Philippine-American War. Plaza Lawton and Lawton Avenue in Manila and Taguig, respectively, were named in his honor. Prior to deployment in the Philippines, Lawton fought in the Battle of El Caney in Guantanamo, Cuba.

Funston was some sort of an adventurer. He first served as a volunteer artillery officer for the Cuban Revolutionary forces as a young man. After volunteering for the Philippine campaign, he was promoted to General and was awarded the Medal of Honor for bravery in combat. He earned his fame by leading the ingenious capture of General Aguinaldo in 1901.

Black Jack Pershing is famous for commanding the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) to Europe in World War I. He earned his spurs by participating in the Battle of San Juan Hill in Santiago de Cuba of Teddy Roosevelt’s and the Rough Riders’ fame. Pershing would later lead the brutal pacification campaign against the Moros of Mindanao, which was the first instance wherein the Americans encountered the Muslim mujahedin. Pershing’s experiences with the Moro led to the invention of the .45 caliber ammunition as the old .30 caliber could not easily cut down an attacking Moro juramentado.

Wood commanded the aforementioned Rough Riders in Santiago de Cuba and would move on to command the US Army’s Philippine Division during the Philippine-American War. He would also triumphantly come back for a stint as Governor General of the newly-conquered territory during the American Colonial Period.

THE TACTICS

The enemy containment strategy used by the Americans in its intervention in both Philippines and Cuba were also very similar. After destroying Spanish naval squadrons in Manila Bay and Santiago de Cuba, the Americans utilized the services of the local revolutionaries to help their cause. Calixto Garcia played that part in Cuba while Emilio Aguinaldo assumed that role in the Philippines. By working together with the insurgents, the Americans successfully cornered and then forced the capitulation of the Spanish forces holed up inside Santiago (Cuba) and Manila (Philippines). In both instances, the Americans denied the local insurgents a much-deserved triumphant entry into the cities where they laid their siege on.

A harrowing interrogation technique which the Americans learned from the Spanish during the Philippine pacification campaign was the savage torture technique called the water cure. Today, it more known as waterboarding. Talking about coming full circle. The Americans now practice this technique in the sunny tropical paradise called Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba on modern day reincarnation of Muslim mujaheddin.

To ensure total control of the countryside, where the insurgent is king, the Americans copied the Spanish tactic called hamleting, which concentrated all local inhabitants inside internment camps. The Americans did not implement this startegy in Cuba, where the Spanish resistance was quick to fold. When the war with Filipino insurgents intensified, the Americans copied Weyler’s brutal methods and forced local inhabitants to consolidate inside concentration camps. Many locals died of starvation and disease.

THE BIRTH OF THE UGLY AMERICAN

While Cubans and Americans amicably settled their differences which eventually led to the granting of independence to Cuba with preconditions, the Americans chose to annex the Philippines, based on the recommendations of the Schumman Commission in 1899 which deemed the Filipinos unprepared for self-government. It appears that the Commission based its decision from a report gathered from American commanders on the ground who had pathological hatred of their unconventional foe and among Filipino elite who feared losing their preeminence in the aftermath of the revolution.

Among the more outlandish claims was that the rebellion was orchestrated by a single tribe called the Tagalogs and therefore did not represent all the other tribes of the archipelago. They also assessed that the Spanish Colony was so backward that the natives could not be expected to govern themselves. Contrast that of course with their assessment of how well-organized the resistance was which usually included the elected officials and police officers of the municipalities and barrios. They neglected to mention that the Spanish have already established local governments, who, more often than not, were members of Aguinaldo’s revolutionary army. It’s not going to be first time that Americans would use faulty intelligence to justify a war as the Invasion of Iraq in the early 21st century would later prove.

The American decision to annex the islands, of course, did not sit well with the locals, who had already pinned down the Spanish forces inside the Walled City of Manila (Intramuros). The local rebel leader Aguinaldo believed the promises made by Dewey and various American contacts in support of his revolution. He repeatedly refused the counsel of his commanders Mariano Noriel and Antoino Luna for a pre-emptive strike on the Americans while they were still numerically weak.

As fate would have it, Nebraska Volunteer infantryman William Grayson shot a Filipino rifleman on 04 February 1899. Based on accounts of those who witnessed the event, Grayson shouted Halt! to the Filipino trooper. The Filipino playfully shouted back at him “Halto!”, which means stop in Spanish. Grayson then proceeded to shoot him thinking it was the best course of action. The first Filipino fatality of the Philippine-American War was Corporal Anastacio Felix of the Fourth Company of the Morong Battalion.

This historic event happened at Calle Sociego in an called Alturas in the district of Santa Mesa, Manila. It now stands close to big shopping mall. A nondescript, largely-unnoticed plaque reminds passerby of the historical significance of the place.

Unbeknownst to Aguinaldo, the Americans had already received instructions from Washington to annex the islands, having paid the Spaniards US$ 20 million in exchange for Cuba, Philippines, Guam and Puerto Rico. They were steadily building up their forces on land, expecting a full confrontation with local insurgents. It would have happened sooner or later as the Americans were just waiting for the perfect opportunity to start a fight.

Following the Santa Mesa incident, General Arthur Macarthur ordered an all-out assault of the insurgent positions backed by naval bombardment by Admiral Dewey’s squadron in Manila Bay. In a single day, the entrenched Filipino insurgents were thrown out of the city limits. The incredulous Aguinaldo refused to believe that he had been duped. Aguinaldo held on too long to the promise made by Dewey in Hong Kong and even tried to arrange a parley with the Americans while his trenches were already being bombarded by Dewey’s naval guns.

Although American historians date 04 July 1902, the day Aguinaldo was captured, as the official end of the so-called Philippine Insurrection, Filipino insurgents fought on until as late as 1913 in some parts of the archipelago. By the time the hostilities had completely ended, more than 10,000 American soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Filipino insurgents and civilians lay dead in pursuit of America’s Benevolent Assimilation of the goo-goos, as they derisively called the inhabitants of the archipelago.

In a war in which the Americans used as an excuse the brutality of the Spanish against the Cubans, the so-called American liberators employed the same level of brutality against the aspirations of the Filipino insurgents to be free. The Filipinos gave the Americans all they had. In a war that the Americans still call as an insurrection, the Americans suffered their worst battlefield losses after the Civil War. Historians have since described the Philippine-American War as America’s First Vietnam.

The Americans won largely due to having superior firepower over the insurgents, but at the cost of considerable loss of American blood, treasure and, more importantly, dignity. For a country that was established by men who risked their lives for liberty, a little more than 100 years later they would savagely subjugate another people with similar yearnings for liberty.

YOU REAP WHAT YOU SOW

The Filipinos were brutally forced into American rule. In Cuba’s case, its love-hate relationship with the gringos would eventually boil over fifty years later. Angry at the imposition of the Platt Amendment which gave the Americans the right to intervene in Cuban politics, Fidel Castro and his little band of revolutionaries liquidated their decades-long grievances against the oblivious Americans.

While the Cuban mambises and their erstwhile American allies did not come into blows in the immediate aftermath of the treachery of the fall of Santiago de Cuba, the real confrontation would take place more than fifty years later. That animosity still exists until today.

The difference between the Philippine and Cuban experience is that the latter won their struggle against the Yankee, when they deposed US-backed tyrant Fulgencio Batista. The Philippines thought it had achieved the same in 1986 when it deposed US-backed dictator Ferdinand Marcos without firing a single shot. However, American influence in the Philippines remains pervasive.

If the recent Philippine efforts to entice stronger US presence in Southeast Asia are to be analyzed, Filipinos have not really removed themselves from the ambit of American influence despite being given independence in 1946. On the contrary, it appears that the creeping fear of Chinese expansion in the South China Sea have pushed the Philippines back towards more American interference in its affairs.