My first impression of Mexico when I first visited the country in 2008 was that it felt so familiar. Since then, I have lived in Mexico for almost two years and this impression has been largely confirmed. The Philippines and Mexico are basically similar countries separated by a vast ocean.

It starts with the language. The Filipino language has more than 200 words derived from the Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. For example, Mexicans call their parents tata (father) and nana (mother). Put the letter “y” at the end of each word and you have the exact words Filipinos call their parents. Mexicans call their namesakes a tocayu, just like what we do in the Philippines. A Mexican taxi will drop you off in the next banqueta (pavement), which means the same in the Philippines.

Moreover, basically every vegetable and fruit in the palenque are known by the same names in the Philippines. Another food for thought. One buys things in both Mexico and the Philippines with a peso, the denomination in which both countries derived from the Spanish.

From chile, achuete, camote, camachile, chayote, cacahuate, tomate, to chico, one would think that he or she was in a Philippine tiangge. This is, of course, what the Mexicans call their market. Sipping hot chocolate while shopping for vegetables makes one realize that, yes, cacao and chocolate are old Nahuatl words too.

The intense folk religiosity is also very similar. Millions of Mexicans troop every year to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico. Mexicans venerate Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, Patron Saint of Mexico. It turns out that Filipinos have also chosen Our Lady of Guadalupe as the Heavenly Patroness of the Philippines. She is known in the Philippines as the Virgin of Antipolo or, formally, Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buen Viaje .

This folk religiosity is perhaps best displayed during the festivities for the Dia de los Muertos. Mexico and the Philippines intensely and fervently venerate the Dia de los Muertos. This is known as Todos los Santos in the Philippines. Mexicans and Filipinos alike troops to the Campo Santo. Strangely, this is the same term used by Filipinos and Mexicans to describe a cemetery. For two days, they bring food, flowers and candles to their departed ancestors.

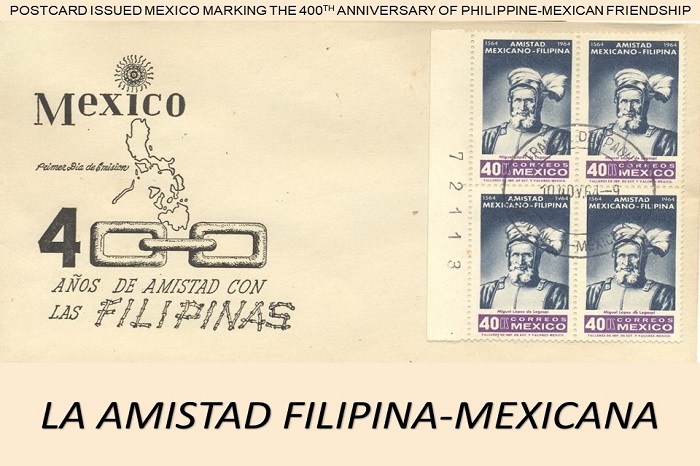

Yet, there is very little appreciation from both sides about Philippine-Mexican historical links. Filipinos know from history books that the country was colonized by Spain for more than 300 years. However, Filipinos have forgotten that they were administered by the Vice-Royalty of New Spain, present-day Mexico.

In Mexico’s view, the Captain General in Manila actually reported to the Viceroy in Mexico City, not to Spain. Hence, the Manila colony was a dependency of the Vice-Royalty of New Spain. This arrangement was to stand until Mexico declared its independence from Spain in 1815.

Mexicans, for their part, also believe that they were directly trading with China. Many Mexicans today think that the galleons sailed directly to Chinese ports. This wrong perception is even reflected in the official marker in Fort San Diego in Acapulco commemorating the La Nao de China. The marker wrongly depicts the galleons as directly sailing to China, not to the Philippines.

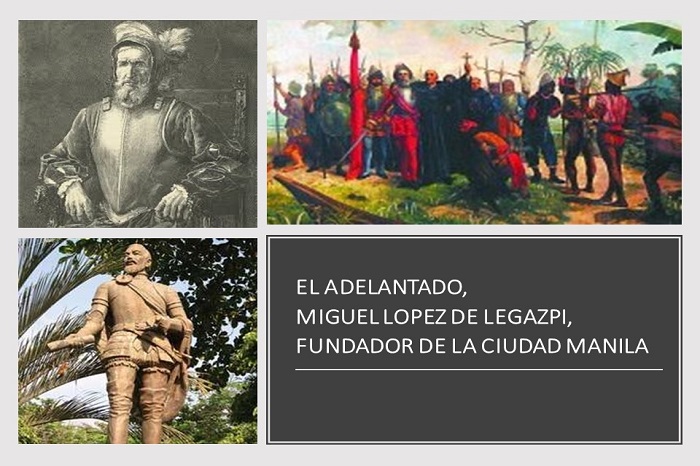

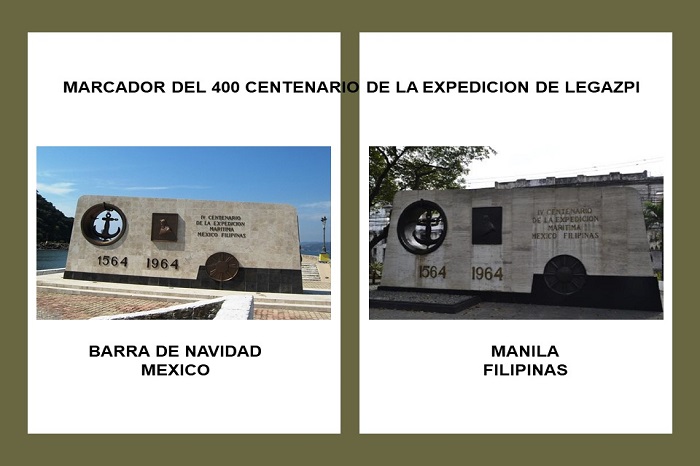

What is clear is that the Philippine Colony would not have survived through the centuries without the assistance of Mexico. When Miguel Lopez de Legazpi sailed from Mexico in 1564 to settle the Philippines, he found the living conditions there very difficult.

The farm animals and horses brought from Mexico did not acclimate well with the tropical heat. Legazpi’s soldiers and sailors had to scrounge food from one island to survive. Chroniclers described living in the Philippines as “cuatro meses de polvo, cuatro meses de lodo, y cuatro meses de todo.” (Translation: Four months of dust, four months of mud, and four months of everything). Todo, in this instance, refers to anything that killed the White Man, including tropical diseases, typhoons, volcanoes, and earthquakes.

Legazpi’s luck turned when he stumbled upon Cebu. This is the same island where Magellan met his fate in 1521. There he learned of the existence of a large Muslim settlement in nearby Luzon called Amanillah. (Or Maynilad, depending on which book one choses to believe). He sent Juan de Salcedo and Martin de Goiti to reconnoiter the Malay community.

Salcedo and de Goiti found Chinese traders (and sea pirates) in Amanillah (or Maynilad). This discovery became the key for the survival of the nascent Spanish colony. The discovery of the Chinese traders, the subsequent discovery of the tornavuelta or the return route to Mexico by Fray Andres de Urdaneta, and the establishment of the Spanish settlement in Manila became the foundation of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade that was to last for 250 years.

The Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade made Manila an entrepôt of commerce between the Far East and the New World. The galleons embarked from Manila loaded with spices, silk, damask, Chinese porcelains, pearls, plants, cotton, indigo, jade, ivory, and lacquer ware. These were paid for in Mexican silver coins which became the dominant currency in the Far East. In return, the galleons brought from Mexico the “real situado” (royal subsidy). These were minted silver coins from the mines of Zacatecas in Mexico and Potosi (present-day Bolivia).

It is important to note that without the real situado, the Spanish colony in Manila would not have survived. The Spaniards did not make the new colony self-sustainable. There was never enough Spaniards in Manila to enable a total conquest of the rest of the archipelago. The Spaniards in Manila were more of adventurers, rather than able settlers. They set off to other parts of Asia to look for treasures and adventures. The demand of labor in Manila was so acute that Spanish authorities even had to import black slaves.

The ingenious solution to the manpower shortage problem was, of course, to source them from the New World. Mexico is merely a four or five month-sail by ship. In comparison, sailing to Spain via the Cape of Good Hope took one year. Hence, the vast majority of colonial administrators, missionaries, and soldiers deployed to the Philippines were Mexico-born Spanish, Mexican creoles and indigenous Mexican Indians.

With so many Mexicans sent to the Philippines within a period of 250 years, it is not surprising then that Mexican language, culture and norms have become integral part of the Philippine consciousness. These are nuggets of wisdom that we should remember as we commemorate the 450th anniversary of the Legazpi Expedition this 2015.