I am constantly reminded of the fact that I am probably the lone gatekeeper of information pertaining to Philippine-Cuban relations at the Department. Basically, I was our last man in Havana. I was tasked with closing down the now-defunct Philippine Embassy in Havana, which closed down for good on 31 October 2012.

This unwelcome designation gets highlighted even more when certain diplomatic occasions arise. Nobody at the Department seems to have kept any records or files about Philippine-Cuban relations. It is as if the closing of our respective embassies were the end of our relations. Old files simply get forgotten or disappear. Sometimes, this could be embarrassing when one realizes they are suddenly needed. (e.g. presentation of credentials of new non-resident ambassador, for instance).

In order to prevent similar incidents in the future and considering the impermanent nature of our work at the Foreign Service, I have decided to publish my own personal take on Philippine-Cuban relations. (P.S. I sprinkled in a lot of my own very liberal views on certain issues that do not necessarily match the official positions of the Foreign Ministry). I presume that this information could now be easily obtained through the World Wide Web. As they say, everything lasts forever in the internet.

Cuban-issued commemorative stamp issued in 2011, flanked by the flags of the Philippines and Cuba.

The fact is, come 04 July 2016, we will be celebrating exactly 70 years of Philippine-Cuban diplomatic relations. This is the date when the Republic of Cuba effectively established diplomatic relations with the newly-independent Philippine Republic. I hope someone on both sides of the hemispheres would recognize that fact. The establishment of formal relations was further cemented by the accreditation of the Philippine Ambassador in Washington D.C. as non-resident ambassador to Cuba.

Cuba’s speedy recognition of Philippine Independence should not elicit any surprise at all. The Philippines and Cuba have long shared parallel histories. Havana was linked to Manila through a nautical superhighway called the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade. The galleons sailed from Manila to Acapulco, bearing riches from the Far East. The same goods were transported overland from Acapulco to Puebla. These were then carried onward to the port of Veracruz in the Gulf of Mexico. Then, these were further loaded into another convoy of galleons, which docked at La Habana before proceeding to Cadiz in Spain.

Spanish colonial port cities: Manila (above) and Havana (below).

The galleons did not just bring riches and goods for trade. They also provided a means for human mobility. Thus, the transoceanic migration between Asia and Latin American was born. Filipinos settled in what is now Mexico and beyond. It was through these galleons wherein the first Filipinos started arriving in Havana as artisans and mariners in the 17th century. The area where the first Filipinos in Havana settled was in the district of Cerro. Interestingly, Cerro now has a park and a street named after Manila (i.e. Parque Manila and Calle Manila, respectively).

The arrival of Filipinos in Cuba continued in the succeeding years. Prior to 1774, the famous tobacco-growing Cuban province of Pinar del Rio was formerly known as Nueva Filipinas. This was as a result of immigration of Filipinos who worked in the tobacco fields, according to local historians of the Cuban province. The Filipinos in Cuba were called Chinos de Manila. This was done to differentiate them from the “real” Chinese, who were called Chinos de Shanghai.

Parque Manila in the Cerro District of La Habana (source: R. Thom)

The Philippines’ special place in Cuban historical lore is also reflected in the fact that both colonies holds the fraternal distinction of being the last Spanish colonies to rebel against Mother Spain. I was always reminded by older Cubans when I was in Havana that Filipinos and Cubans were hermanos de la lucha. It is indeed very interesting to note that in the second half of the 19th century, the Philippine and Cuban independence movements passed through nearly identical courses.

The Cubans started their fight for independence in 1868 which lasted for the next ten years. Thus is become known as the Ten Years War. Cuba’s first try at Liberation ended in a truce with Spain in 1878. This was just in time for the establishment of what is known in the Philippines as the Madrid-based Propaganda Movement.

Records left behind by Filipino ilustrados state that the nascent Filipino nationalist movement was influenced by the boisterous Cuban expatriate community in Madrid. Filipinos freely congregated with Cubans to exchange views. This familiarity with the Cuban struggle would be manifested later when the newly-established Philippine Revolutionary Government unfurled a flag and constitution that were similar to their Cuban counterparts.

The leaders of the Filipino Propaganda Movement in Madrid, 1890

The Cuban-Filipino revolutionary links did not end with the Propaganda Movement. Historical evidence shows that, based on research conducted by the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias (FAR) of Cuba and published in its magazine called Verde Olivo, the leaders of the revolution in Cuba and the Philippines were directly corresponding with each other. They were sharing tactics and, in some instances, sending requests for weapons. As proof, Cuban military historians have published letters exchanged between Filipino General Mariano Llanera and Cuban Revolutionary leader Maximo Gomez.

These links were further continued during the exile of the Revolutionary Committee of General Emilio Aguinaldo in Hong Kong. Again, based on FAR’s records, the Filipino exiles secretly rendezvoused with representatives of the Cuban and Puerto Rican Revolutionary Movements in Hong Kong. Cuban military historians have also recently recognized the participation of many Filipino volunteers in the Cuban revolutionary army. These were mainly Filipino seafarers, who had settled in Cuba.

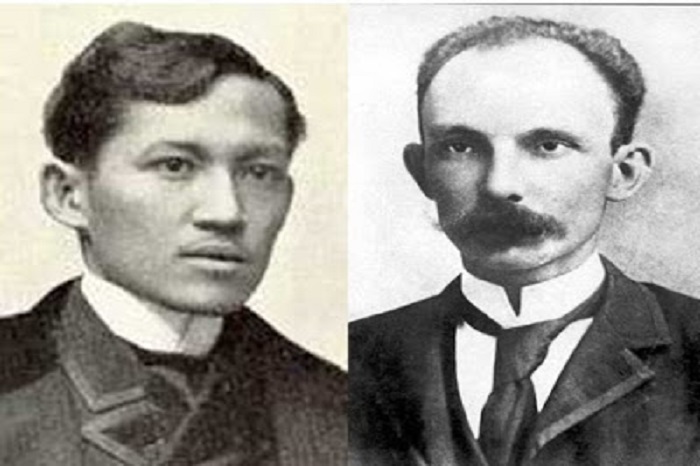

Revolutionary contemporaries: Philippines’ Jose Rizal (left) and Cuba’s Jose Marti (right).

Interestingly, Cuban national hero Jose Marti and Philippine national hero Jose Rizal also shared near parallel lives. Both were propagandists, masons, writers and poets. They also became martyrs in their respective struggles. Moreover, Dr. Rizal had his own personal rendezvous with Cuba. He was on his way to Cuba to become a medical volunteer when the Spanish authorities arrested him for subversion.

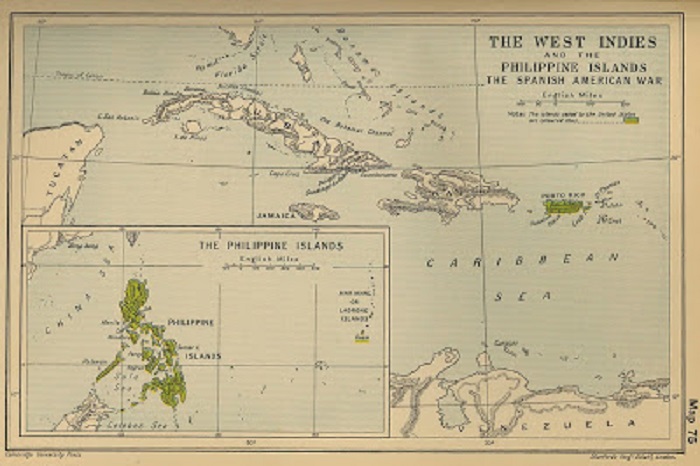

The Philippines and Cuba also shared near-identical experiences during the Spanish American War in 1898. Using the pretext of vengeance for the explosion of USS Maine docked in Havana harbor, the Americans intervened against the Spanish in both colonies. Cuba has always been coveted by the US as a possible Caribbean possession. Meanwhile, the Philippines became of strategic value to American expansionists who wanted a foothold in the Asia Pacific. Both Cuba and the Philippines were relinquished by the Spanish to the Americans by virtue of the Treaty of Paris in 1898.

1898 Spanish American War Map showing the Philippines and Cuba (source: maps.nationmaster.com).

While Cuba was granted its independence in 1902, the Americans kept the Philippines as a colony until it was finally given its independence in 1946. The Filipinos went on to fight a bloody struggle against the Americans in a period that US historians call as the Philippine Insurrection. During this struggle, General Aguinaldo and the Philippine independence cause received wide support and media coverage among Cubans.

In effect, 04 July 1946 was the culmination of the long and winding bilateral struggle by both the Philippines and Cuba to be recognized as full-fledged members of the league of independent states. Ironically, this historic date also happens to be the Independence Day of the United States of America, the colonial power whose expansionist policies in 1898 so severely affected the histories of both Cuba and the Philippines.