Something interesting happened when I attended the “Colloquium on the Pacific” hosted by the Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas of the Institute Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM). The event celebrated the 500th anniversary of the “discovery” of the Pacific Ocean by the Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa. At the event, I had the honor of meeting Don Benito Legarda, one of the Philippines’ most prominent historians. Dr. Legarda gave me interesting insights regarding the links of Manila and Havana.

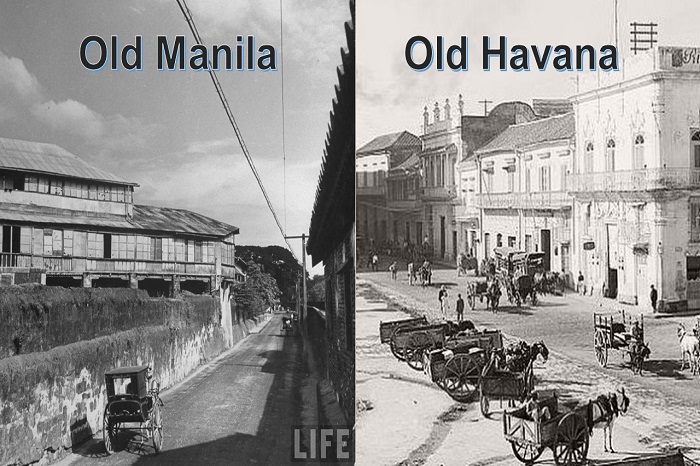

The term “discovery” is a misnomer because the Aztecs already knew of the existence of what we now call the Pacific Ocean. Still sprightly and lucid at 87 years old, Don Benito is basically a walking encyclopedia. I took the opportunity to pick his brains on what Manila was in his youth. He was a young man when World War II happened so he had a very good recollection of how Old Manila was during the pre-War period, fondly called Peace Time in the Philippines.

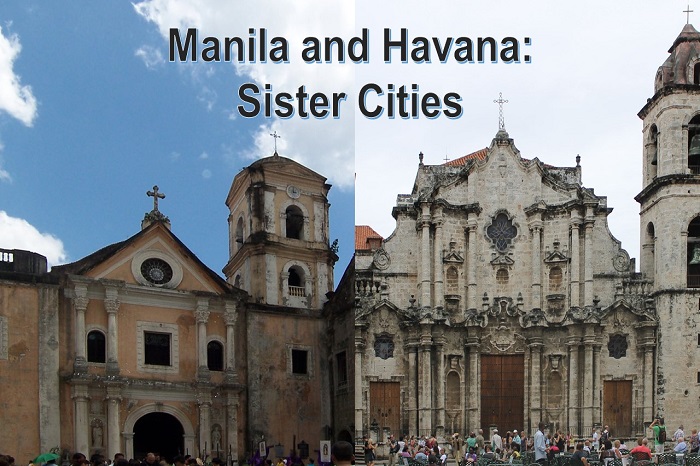

I have always wondered how Old Manila would have measured up to the other Spanish colonial cities such as La Habana Vieja. Manila and La Habana were former crown jewels of the Spanish Empire. Both were among the last imperial possessions that Spain tried desperately to keep. Manila shipped the riches of the Far East to the Spanish Empire by way of Mexico. These same products were then transported to Spain via galleons that pass through La Habana. In essence, the two cities book-ended the two extremes of the profitable Spanish galleon trade for nearly 300 years.

I have read many times that by the 1930s, the old Intramuros of Manila was already decaying. Many of the old families who used to live in the walled Spanish city have left for the nearby arrabales of Ermita, Malate and Paco. American colonial authorities decided to retain the city’s walls while renovating its antiquated sewerage system. The end result was that the ventilation inside the walled city was constricted as the sea breeze could not freely circulate inside the city. It was not a surprise at all that the old city was a known breeding ground of nasty diseases during the colonial period.

“It was a really beautiful city, a city of churches,” Don Benito recalled of the old Walled City of Manila. By the 1930s, no single family owned each of those colonial homes. They were already compartmentalized. Different families occupied different floors, sometimes different rooms in the same floors. Many of those residing in the walled city were natives. Many were students of the nearby universities located inside Intramuros. It was a sign of the times. Manila was at the point of bursting its seams and expanding outward. The rich were moving out in droves to the suburbs.

“It was the fire that destroyed them, not the bombs,” he recalled what happened in World War II. American bombs apparently ignited a huge conflagration that consumed Intramuros. The fire had spread rapidly because the colonial homes where constructed of hardwood and stone. I have often wondered what Intramuros would look like if it had avoided the cataclysm of 1945. La Habana Vieja has been able to keep most of its charms despite the age and decay. Manila, on the other hand, is a different story.

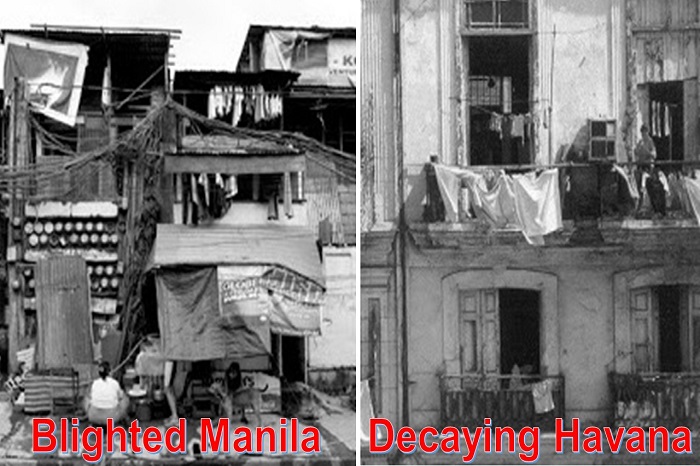

Gauging from the deterioration of its other historic colonial districts such as San Miguel, Quiapo and Santa Cruz, having been left to rot by their former owners and now overrun by squatters, Intramuros would have probably gone the same way. Heritage conservation is not something that Manileños are exactly very strong at. On the other hand, La Habana Vieja is a masterpiece when it comes to heritage conservation. We have much to learn from the Cubans.

My views on La Habana Vieja and Intramuros piqued Don Benito’s interest. Lo and behold, he had been to Havana in 1956 before Castro took over. He was in his late 20s then. I asked him what he thought about the city. “Very touristy,” he told me. Casinos and bars catering to American tourists abound. The atmosphere was attuned to the needs of a certain type of tourist, someone who would enjoy the pleasures of, let’s say, Reno, Nevada or Las Vegas. A very decadent city it was, according to Don Benito. I could tell that his recollection of La Habana wasn’t very memorable.

La Habana Vieja, it seems, brings contrasting memories to different people. Those who stayed behind after the Batista’s ouster remember a historic center that was decaying and left behind by the times. On the other hand, those who left the island to flee Castro remember a remarkably different city of eternal beauty.

The truth, it seems, lies in between. La Habana Vieja can be both the decaying city on one hand, and the beautiful colonial treasure on the other. One just has walk a few meters away from the “pedestrianized” Calle Obispo to the nearby alleys to see the different views. One one side, many of the buildings have been restored, while the other area rapidly morphs into a “favela”-like atmosphere of crumbling edifices.

It was the same in 1956, I presume. As much as rich Cubanos remember that period as the Golden Age of Cuba, majority of the city’s residents wallowed in extreme poverty. La Habana was both the city of extreme wealth and of hideous poverty. In essence, both sides remember the same city, but from a very distinct perspectives. Don Benito’s perspective was that of a neutral observer. He came as a tourist but not in the usual sense as was common at that time. He was not there to booze it up and party. He was a connoisseur of culture and history. The La Havana Vieja that he saw was at the height of its decadence. As early as 1956, he already felt the underlying social tensions that brought Fidel Castro to power in 1959.

The story of post-war Intramuros is basically the same as La Habana’s, although its gentrification started way earlier. Once a symbol of Spanish exclusivity, the Walled City had become by the time it was wiped out in 1945 a shell of its old self with many of its former inhabitants fleeing to the surrounding suburbs. After World War II, many homeless inhabitants from everywhere poured into the ruins of the old city. They established ugly squatter colonies that still exist today. Parts of Intramuros remains blighted by extreme poverty to this day.

Habana Vieja did not suffer violent war destruction as Intramuros did. However, it can be argued that, through the years, a large part of its colonial center has been turned turned it into a massive “favela.” Many of its grand edifices were converted into tenement housing. Fidel Castro’s revolutionary government relocated the homeless to vacant dwellings of the rich who departed in droves.

This was a fine idea at first. But, this was a terrible idea in retrospect. The new occupants could not afford to pay for the upkeep of the buidlings, while the government was too broke to fund them. For example, I visited the home of a Cuban, who was formerly married to a Filipino seafarer who lived in Centro Habana. She told me “It’s like being in a squatter area, isn’t it?” The difference being their houses were made of stone and concrete, but their plight is the same.

It is interesting to note that despite the distance and the lost links, both Manila and La Habana have a lot of things in common – both good and bad. It is not a surprise at all that both cities signed a partnership agreement in the 1990s. Manila can learn from La Habana on how to recover its old glory. The Intramuros Administration (IA) is trying mightily to restore Old Manila. The recent restoration of the former Ayuntamiento is a step in the right direction. Popular walking tours through the old city are now en vogue, contributing to the rebirth of the old city.

Filipinos may not know it, but our countrymen have been part of La Habana’s history since colonial times. A Parque Manila and a Calle Manila have been named in the Cerro district in honor of the Philippine capital city. It was in that part of the city where the Chinos de Manila first settled. Their descendants are now part of the Cuban society at large. The name Manila is now an indelible part of La Habana.

When I tell younger Cubans what my nationality is, they are mostly left scratching their heads. But I am heartened by the fact that elderly Cubans have very fond recollections of the Philippines. They call us their “hermanos de la lucha” or brothers in arms, referring to our common struggle against Spain. What happens after the older generations die off? I guess we will be left scratching our heads.

Things are changing, in terms of cultural diffusion, at least in Manila. Manileños get to enjoy the bohemian vibe of Cafe Havana while sipping mojitos with a Cuban cigar in hand. Interestingly, we are now importing a lot of those cigar leaves from Cuba to be rolled into handcrafted smokers by Filipino hands. Havana Club rum is also widely available in Manila now, which is good news for a people known for being teetotalers. Even the Cuban lechon is available now in a country where the fare is as ubiquitous as the “jeepney.” Guayaberas (called Havana shirt in Manila) are starting to be patronized by many Manileños due to its suitability to the humid weather albeit “bordado” in distinctly Filipino style.

A good number of Manileños, no slouch dancer themselves, are learning how to dance salsa, just as their parents and grandparents did with the Chachacha and Danzon. I would not be surprised if Filipino youths are also dancing to the tunes of reggae-ton in the city’s discotheques. Cuban culture is alive and well in the Philippines, thanks to globalization and the social media. There is hope after all that we will get to keep our links despite trying really hard not to. Today’s Facebook generation will do its best to keep it alive.