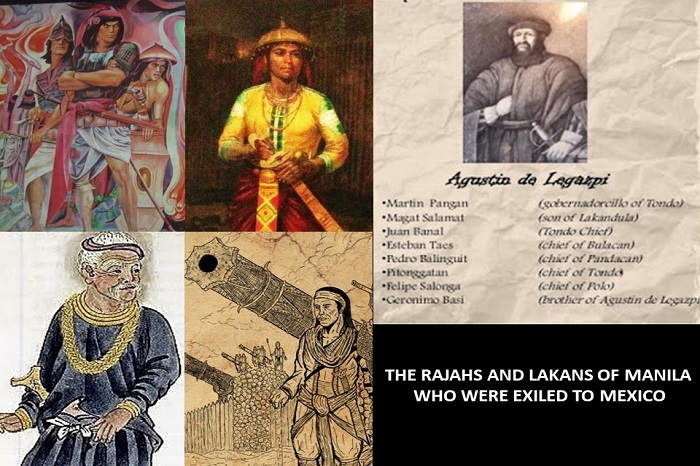

The first recorded arrival of natives from the Philippines to Mexico was necessitated by the first big revolt against Spanish colonizers in Manila. This revolt was led by almost all local datus or chieftains of note in and around Manila in 1587-1588. One of the chief organizers was no other than the mestizo grandson of Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, whose hispanized name was Agustin de Legazpi. He was the product of the marriage between the son of a Tondo prince and Legazpi’s own daughter.

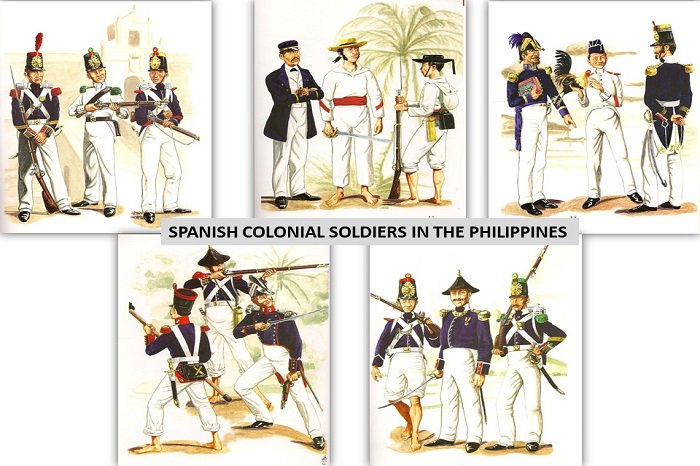

Spanish tercios under Legazpi faced tremendous challenges in the Philippines, including a revolt by Manila’s native chieftains, and piratical Japanese and Chinese.

Hence, the first subersives and deportees became the first Filipinos in Mexico. The list of these deportees include such luminaries as Pedro Balingit (Lord of Pandacan), Pitongatan (Prince of Tondo), Felipe Salonga (Lord of Polo, present-day Valenzuela), Calao (Commander-in-Chief of Tondo), and Agustín Manuguit (Minister of Tondo). Records show that these subersives and deportees arrived in Mexico in July 1589.

Through the years, the Spanish used New Spain as dumping ground for Manila’s subersives and deportees, and vice-versa. When it was Mexico’s turn to revolt against Spanish authorities during the decades-long Mexican War of Independence, Mexican revolutionaries captured by Spanish authorities were promptly shipped to the Philippine islands. The most famous of these Mexican deportees was Queretaro native Epigmenio Gonzalez Flores who was deported to Manila in 1810 along with 40 other subversives and deportees.

Gonzales Flores was an important aide of Father Miguel Hidalgo Costilla in the Mexican revolutionary movement. Gonzalez Flores, by force of will despite being penniless, was able to return to Mexico via Spain in 1838. This was long after Mexico gained its independence in 1821. He had been in prison for more than 25 years. This took a severe toll on his physical and mental health. Gonzalez Flores has since been recognized by the grateful Mexican nation as among the main players of the 1810 Mexican War of Independence.

The list of conspirators of the 1587-1588 Manila Datus’ Rebellion, include Legazpi’s own creole grandson and most of Manila’s chieftains.

The emergence of the Mexican War of Independence in 1810 was a turning point in Philippine-Mexican relations. Spain was anxious to keep the Philippines from being afflicted by the independence fever. Spain did its best to remove Mexican and Philippine links. That was easier said than done. By then, a vast number of Filipinos were living in Mexico. Many of these Filipinos in Mexico, per historical accounts, participated in the Mexican War of Independence of 1810. One of the most famous of these Filipinos was Ramon Fabie, who was a lieutenant colonel in Father Hidalgo’s Valencia Regiment in Guajanuato.

Fabie was a scion of a rich clan from Paco (a settlement in Manila). He went to study mining engineering at the Colegio de Mineria in Mexico City at age 16 in 1802. His father was a lawyer for the Real Audiencia in Manila. In 1810, Fabie was in the silver boom town of Guanajuato. There, he joined the rebel Mexican Army, mainly composed of miners from the nearby Valencia mines.

Fabie took part in the defense of Guanajuato against a counterattacking Spanish force in November 1810. The Mexican insurgents were defeated. The surviving rebel officers, including Fabie, were hanged in front of the town’s infamous Alhóndiga de Granaditas. The grateful Mexican government later recognized Fabie by naming a street in Mexico City after him.

The 1810 Mexican Revolution involved many Filipinos living in Mexico, including Ramon Fabie, who died in Guanajuato.

The Spanish were not without basis when they feared that the Mexican War of Independence would cause political upheaval in the Philippines. The ordinary foot soldiers of the military in the Philippine Islands were mostly composed of recruits from New Spain and other Spanish Latin American colonies. After the declaration of Mexican Independence in 1821, the loyalty of these Mexican and Latin American soldiers were now under a cloud of suspicion.

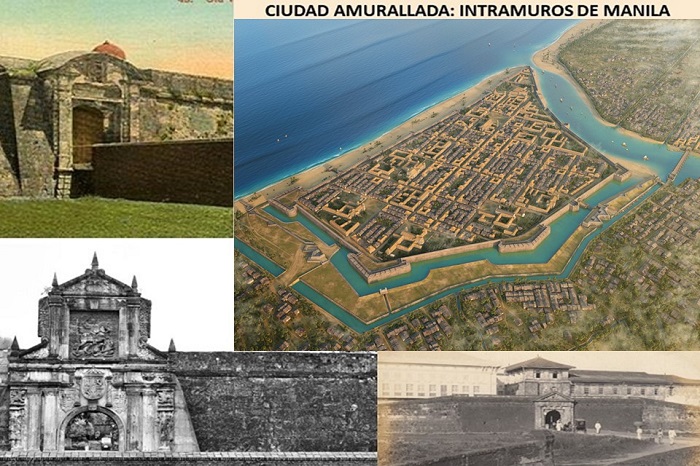

Spanish authorities sought to sideline these Mexican and Latin American soldiers by removing them from important military posts. In June 1822, the Mexican creole Andres Novales, a captain in the King’s Regiment, led some 800 other Mexican and Latin American soldiers in revolt. Initially, the subersives captured the Palacio del Gobernador and some other important government buildings in the Walled Spanish City of Intramuros.

Captain Novales was no slouch even if he was stuck in the rank of a captain. He was probably the most experienced soldier in the Philippines at that time. He had previously served under the Spanish Army against the revolutionary forces of Simon Bolivar in Latin America. Then, he served in the Napoleonic Wars in Europe. Upon capturing Intramuros, Captain Novales declared himself Emperor of the Philippines. He planned on installing a constitutional monarchy in the mold of Napoleon Bonaparte.

A view of the Walled City of Manila, the Intramuros, during the Spanish colonial period.

However, Captain Novales’ attempt to completely defeat the Spanish forces was thwarted by his very own brother, Mariano, who was a lieutenant of the Spanish Army. Lt. Mariano Novales refused to open the gates of Fort Santiago for his brother’s subersive force. This move deprived the subersives of possession of cannons in its arsenal.

Later, Spanish forces counterattacked with thousands of local Macabebe (from Pampanga province) auxiliaries. The counterattacking Spanish-led force captured Captain Novales and other subversive Mexican officers. Most of the captured subversives were subsequently executed. This was not to be the first time that Macabebe Forces came to the aid of Manila throughout Philippine history. These feats of courage have earned the Macabebes the monicker of “ever-loyal” from the grateful Spanish authorities.

The sad story of Captain Andres Novales is never taught in Philippine schools today. It is high time for the Philippine Government to give Captain Novales the credit that he deserves. Captain Novales and his intellectual partner during the fateful revolt, the self-styled Conde de Manila Luis Rodriguez Varela, were the first ones to use the term Filipinos to define the citizens of the Philippine Islands.

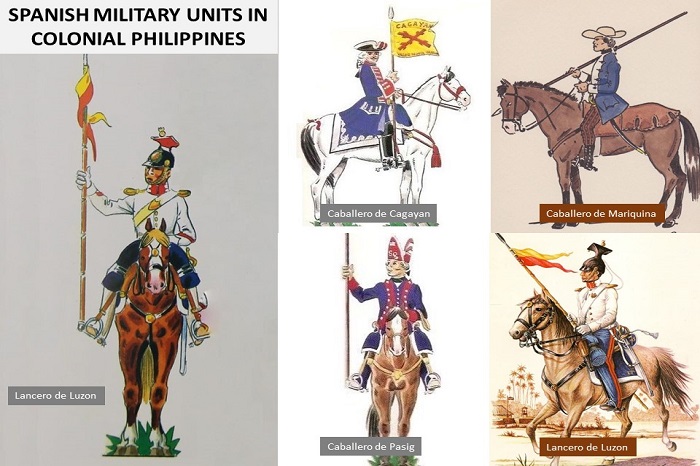

The Spanish colonial troops at the turn of the 19th century were mostly made up of soldiers from Mexico and Latin America.

In effect, Captain Novales and Rodriguez Varela were the authentic First Filipinos. Despite their Mexican creole background, they were among the first inhabitants of the Philippines to believe in the possibility of a Filipino state. The survivors of the Novales Rebellion were subsequently expelled by the Spanish. In December 1823, a ship called Flor del Mar arrived in San Blas, Sinaloa State in Mexico, carrying with it the subersives and deportees who took part in the revolt.

It is said that Father Miguel Hidalgo, while he was still alive, saw it almost as an obligation to help, even militarily, the Philippines achieve its own independence from Spain. In the process, Father Hidalgo wanted integrate the Philippines under a single government with Mexico.

The Mexican General Agustin Iturbide secretly sent a mission to Manila to determine if the islands were ripe for a revolt. However, the Mexican secret agents reported back to Mexico that the Philippines was not yet ready for a revolution. This was apparently a mistake since Captain Novales would led his revolt in less than a year.

The various military units posted in colonial Philippines were: Granaderos, Cazadores, Tiradores, and Fusileros, among others. These were mainly Mexicans and Latin Americans.

Links between General Iturbide’s secret agents and the Novales uprising have not been sufficiently established by historians. This despite the clear proximity in the progression of the two actions and of the fact that the Novales rebellion was mainly Mexican-led. A subsequent conspiracy led by Mexican creoles Vicente and Miguel Palmero was discovered by Spanish authorities in Manila in 1825. This action bore the hallmark of a plot orchestrated from Mexico. Yet, the conspiracy did not bear fruit.

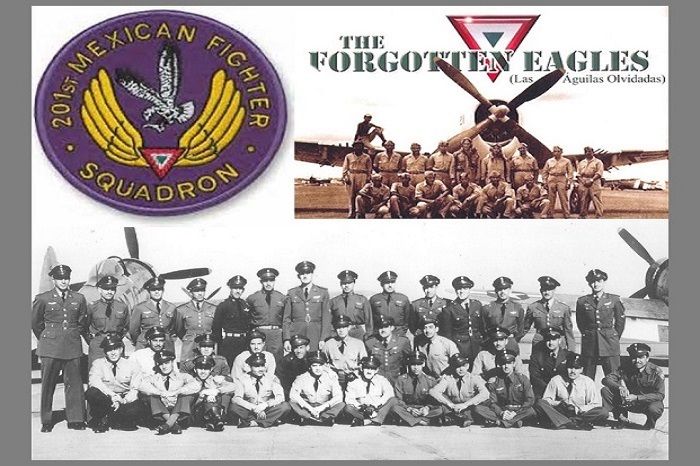

True to Father Hidalgo’s wish, direct Mexican participation in fighting in the Philippine Islands actually happened. This was during World War II when the Mexican Government sent the 201st Mexican Fighter Squadron to participate in the Liberation of the Philippine Islands from Japanese forces in 1944.

Squadron 201, also known as the Aztec Eagles, participated in the Liberation of the Philippines in 1944-1945.

More popularly known in history as the Aztec Eagles, this Mexican Force was the only instance when the Mexican Government ever allowed its forces to fight outside of Mexican soil. Thus, Father Hidalgo’s dream of sending military assistance to the Philippines came to fruition more than a 100 years after the promise was made.